[This post was once published in the now-superseded ezine ‘Dynamic Living’ under the title: ‘Learning to live with ‘Stupidity’]

We’ve all said it, often with additional expletives: “How could they be so stupid?!” “They” are often in authority – the government, the boss, the school board – but they can also be peers or subordinates. It seems that friends, spouses, children, and employees are all capable of behavior that strikes us, uncharitably, as ‘stupid’.

For gifted individuals, as for all those who are unafraid to see that the emperor is indeed naked, living in a ‘stupid’ world is particularly painful. Many things that could improve life are so obvious and yet so overlooked. This article takes a look at the reality behind ‘stupidity’ and what we can do to reduce its impact on ourselves.

‘Mediocrity Rules’: Get used to it!

If you’ve ever felt that this is a mediocre world society run by and for mediocre people, you deserve credit for your readiness to see the truth, even when it hurts.

After all, if everyone in the world is to survive, its tasks and requirements have to be manageable by very nearly the least capable among us. That means such tasks are unlikely to challenge or produce results that consistently satisfy the healthy demands of the most highly-resourced individuals.

P.T. Barnum famously declared that “no-one ever lost money by underestimating the intelligence of the American public”. That same observation applies equally to the world at large, with the result that those motivated by money and temporal power focus their efforts on the lowest common denominator. This doesn’t leave much over for those who would prefer something more challenging than a night out at “Jurassic Park” followed by a Big Mac.

A basic principle

The sad truth inherent in the above example helps to explain why the more able or visionary among us feel so lonely, rejected and undervalued. We are genuinely in a minority, thinly distributed among much greater numbers of humans with less of every quality – thoughtfulness, integrity, reflectiveness, vision, insight, etc – we hold dear.

This sounds shocking to those of us brought up to believe in democracy and the belief that we are all equal. However, equal rights to exist as best we can are not the same as equal personal resources. Those are in the hands of mother nature, the universe, or God, depending on your preference, and they are not evenly distributed or evenly applicable.

Those most richly endowed with personal gifts are in a minority, so it is unlikely that they will predominate in power or even influence. It seems as if they should – after all, evolution alone might be expected to prefer the exceptional over the ordinary – but evolution, like democracy, takes a more cautious middle path. It’s just not fair! And it can be painful to endure.

What makes it hurt?

The reason for the pain can be shown by example. A good many sci-fi films have included a sequence in which a robot, given two opposing instructions, goes into a spin shouting: “Does not compute!” and eventually blows its own head off. Our human equivalent is called ‘cognitive dissonance’ – the attempt to hold two opposing ideas – and it causes us great pain.

You can see the signs of this in someone given conflicting instructions. Perhaps they’ve been told they have to produce a piece of work by a given time and simultaneously informed that an essential resource is unavailable to them. They stop in their tracks, wrinkling their forehead, scrunching their face, scratching their head. They’re simultaneously stressed and perplexed. And it hurts.

I believe a similar pain is caused when we experience the conflict between what we can see of how life could be and how it actually is. Call it: ‘existential dissonance’. Of course, the reality is that it can’t be other than the way it is, but this doesn’t mean that our visions are based in unreality. My sense is that we typically incorporate the tools and structures that are already to hand when we develop our visions of a practical utopia. It makes it all the maddening when ‘they’ get it wrong.

Our task is to find a way to live with this painful reality.

Recognize and accept

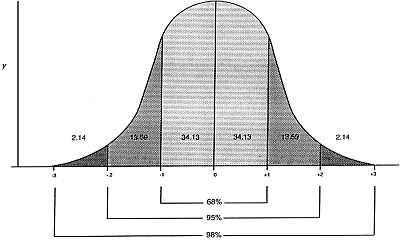

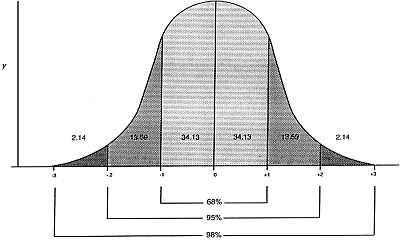

Most people have some acquaintance with the statistical concept called a normal or “bell” curve. This curve results from the observation that most direct measures of varying traits in human beings and most psychological measures, such as IQ scores, have been found to approximate closely to a mathematical model called the ‘normal distribution’.

The graph of this normal distribution is a continuous, symmetrical, bell-shaped curve. Frequencies tend to concentrate around the median and become fewer and fewer at either end, resulting in a frequency curve which is high in the middle and low at the ends.

The bell curve looks like this:

The Normal Distribution

The numbers at the bottom aren’t a measure of anything specific. They are simply to be used for reference. The mark in the center is the median, where ‘most people’ predominate. Those at the right hand end of the curve have more of whatever is being measured than most, while those at the left hand end have less.

You could imagine the bell as a moving entity, going to the right. Whatever it encounters, the right hand end (where the the pioneers and early adopters live) finds it first, the bulk meets it a little later, and the tail reaches it last. Thus inventions form in the mind of the inventor (on the right), then reach the university research lab, then trickle into industry research labs before finally finding their way out as products into the mass of the public. Late adopters – those at the left hand end – will acquire ‘the latest things’ just before they turn obsolete.

The point of this bell curve is that it applies to everything. It can be the distribution of intelligence, or integrity, or independence or autonomy or awareness; it can be physical capabilities or IQ or EQ. It stands to reason that if you are of exceptionally high intelligence, integrity and intellectual courage, then you are going to be sitting right up at the front end of the bell curve of those qualities.

That would mean you’re likely to be pretty lonely. It means you’re not going to be immediately understood by more than a handful of fellow humans. Worse, it means your contribution probably isn’t going to be valued by many people because most of the world (all those ‘behind’ you on the curve) won’t recognize its significance.

If you want to maximize your chances of being rich, happy and successful in every way, make sure you’re born into a space round about the +1 mark. Then you’ll be just ahead of the masses sufficient to profit from them coming along just behind, and not so far ahead that their relative lack of vision will bother you too much.

A practical example of the impact of the normal distribution is my practice. The psychological types who predominate among my clients are the IN** types and those numerically close to them. Those four types, out of a possible sixteen, total only 10-14 percent of the USA and probably world population.

This means my constituency is only about a quarter of the size it would be if we were ES** types, who add up to nearly fifty percent of the population. It also means that if you are an IN** type, you must look harder to find like-minded individuals to partner with at work or home. (You might find them among the varied gatherings of those classified as ‘core cultural creatives’).

Generally speaking, however, if you feel lonely it’s probably because you’re seriously outnumbered by people who don’t think or feel like you at all.

What can you do about it?

Such an imbalance calls for a considered response. I feel sure that as children we were all full of our greater vision and insight and shouted it loudly from the school desk or the dining table. Until, that is, we learned that it wasn’t wanted. Then we went into a state of hurt and resentment and a sort of ongoing bafflement as to the nature of these weird people who couldn’t – or wouldn’t – see the obvious.

Sometimes, our caretakers were so blind they actually put us at risk. Pretty scary. This brought additional intensity into our experience of existential dissonance. Often, we would compensate by assuming it was us who were wrong in every way.

Today, we can easily find ourselves in similar positions: with workmates, acquaintances, and even our spouses. This is very troubling, recreating the old mix of pain and frustration at not being able to make ourselves understood.

Managing this pain is much easier if you can find yourself in a mental and emotional place of lowered expectations, both for yourself and for others. Some of these thoughts might help move you there:

* Remember, wild animals that are outnumbered and not respected by the rest of the animal kingdom tend to lie low until they‘re sure it‘s safe to proceed. Self-protective IN-types do likewise!

* Recognize where your understanding is on the bell curve and accept the fact that those more than a short distance behind you are simply never going to understand what you‘re talking about. Yes, this does have huge implications.

* Acknowledge your difference to yourself and don’t try to bring the full force of your competence to bear in an environment designed for less-resourced individuals. It can only bring you grief.

* Accept that you aren’t going to change the world of mediocrity you’re forced to live in. Find a task space, a hobby or preferably a career, where you can genuinely stretch yourself and be challenged by the possibilities. This is easier for academically-oriented individuals than for action-oriented ones.

* Be ready to discover and acknowledge the aspects of life in which ‘they’ sit further toward the front of the curve than you do. In acceptance, perhaps, or courage or pragmatism, or physical strength.

* Accept that in a couple, the person further back in the curve, no matter what the subject, is going to set the operating standard. This is because the one behind cannot easily adjust their position forward, but the forward-dweller can operate at a stage further back. In real terms, this control-from-the-rear dynamic is often seen in couples whose risk-tolerance is widely divergent. There, the most risk-averse partner controls risk-related issues and can apparently prevent the readier risk-taker from achieving his or her goals.

* Don’t make the mistake of believing that your competence can compensate for a work- or love-partner’s relative incapacity. Forward-dwellers are often so lonely they underestimate their own exceptional qualities and embrace less adequate others, mistakenly believing they can fill the gap or bring their partner on. Sooner or later, this breeds resentment and ongoing recrimination, resulting in partnership breakdown.

* Recognize that the wayward behaviors that forward-dwellers are prone to – such as addictions, eating disorders, alternative sexual practices, compulsions, paranoid responses and reclusiveness – are a natural response to being in a very difficult position. These behaviors may not make it any easier to make friends, but they aren’t anything to be ashamed of in themselves.

* Most of all, don’t blame yourself for what you cannot change. Recognize that your powers to effect change are disproportionately small compared to your vision and understanding and that you didn’t make it this way. Push where you can but don’t blame yourself if the wall doesn’t budge. Put real effort into finding others like yourself and be creative in your adaptations to life in what amounts to an alien world.

* Trust the universe to know best. One of my favorite bumper stickers reads: “Don’t believe everything you think.” Like many people who sit and think a lot, I have a tendency to imagine I have a personal line to the truth. (‘Eureka’ moments come so much more frequently if you don’t risk exposing them to others’ inspection!) However, it’s worth remembering that all our ‘thought’ is just conjecture. None of us have the superior perspective to truly understand this universal system that’s been chugging along contentedly for around 14 billion years.

* Oh yes: a healthy sense of humor helps, too.

Summary

One of the intrapersonal dynamics I encounter very frequently arises after a client has seen something clearly yet has had their observation refuted. Alone, perhaps even disparaged, they then attempt to explain it away to themselves as some error of their own.

In order to live the life and produce the work of which only you are capable, you must develop a substantial faith in your right to your own judgment. A good starting point for this is to accept that you feel differently and see differently for a good and natural reason: you are different.

As you grow in confidence and articulation, you will find others of like mind who will respect and appreciate you, just as you do them. Your peers are not plentiful but they are there. Don’t be afraid to let them know about you, too. Then the blindness of so much of the world won’t seem so painful.